Historical Background

China is “carved up like a melon”

The Opium War of 1840 marked the beginning of a century of humiliation and turbulence for China. The country submitted itself to incursion and occupation over successive decades by various imperialist powers. The last Chinese dynasty, the Qing, fell in 1911 and was replaced the year after by a republic rent apart by rival warlords and political factions. Weakened by corruption and unable to defend itself through its own ineptitude, China was forced through a series of treaties, referred to as the “unequal treaties” in Chinese (不平等条约, bu pingdeng tiaoyue), to pay indemnities that would drive it further into bankruptcy, open up ports to foreign trade and allow foreign concessions to be established with full extraterritorial rights. The country was effectively being “car ved up like a melon” (瓜分, guafen).

‘The Shandong Problem’

Of particular concern was the eastern province of Shandong. Largely controlled by the Germans, Shandong was being eyed by the Japanese who saw it as a gateway to the vast north-east of China, or Manchuria as it was then known. The opportunity to thwart Japan’s expansionist ambitions presented itself during the First World War. Although looked upon as the ‘European war’, the Chinese government offered its support to the Western Allies. The thinking was that, if Germany were defeated, China would earn a place at the peace talks, regain control of Shandong, reaffirm itself internationally and cast off its humiliating label of being ‘the sick man of Asia’.

Map of foreign influences in China c.1845-1945

Three offers of assistance were made. On the first occasion, shortly after the outbreak of war in 1914, China proposed sending troops to join the British assault on the Germans in Jiaozhou Bay on the Shandong coast, but this was rejected by Sir John Jordan, the British Minister in Peking. Britain thought the war would not last long and, in any case, perceived the Chinese army as being too weak to be of any use. Besides, China was a neutral country and its participation would therefore have compromised its position.

At the second attempt a year later, a mixed cohort of soldiers and labourers was suggested, but the proposition was also rebuffed by the British, this time under pressure from the trade unions at home who feared the presence of Chinese workers would have an adverse impact on their own jobs.

Still, a third offer – this time, of workers only - was made. By the middle of the following year, the French government began to transport Chinese labourers to Europe via the Indian Ocean and through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean.

It was during one of these journeys, in February 1917, that the French transport ship SS Athos was torpedoed by a U-boat. All 543 Chinese labourers on board perished. The tragedy gave China the pretext it needed to declare war on Germany and involve itself officially in the fray. By then, however, Britain had already had a change of heart. During the summer of 1916, the Battle of the Somme - one of the bloodiest conflicts in human history - had claimed such high casualties amongst the Allies that Britain could no longer afford to ignore China’s overtures of help.

“Shandong dahan”

The question was what sort of men should be recruited and from where. Hong Kong was an obvious choice, for it was now a British colony, which would mean no bureaucratic interference from the Chinese government or violation of its neutrality. Men from the south were slight of stature, however, and would be unable to withstand the harsh climes of northern France and Flanders. By contrast, those from Shandong were sturdy fellows. Commonly known as shandong dahan, (山东大汉 literally, ‘strapping Shandong men’), the British War Office recognised that they were “inured to hardship and almost indifferent to the weather”.

Furthermore, they could be easily shipped out of the province without Chinese obstruction. The port of Weihaiwei, on the tip of the Shandong Peninsula, had been leased by the British in 1898 and was used primarily as a summer anchorage for the Royal Navy’s China Station and a health resort for British expatriates. Conveniently, the Germans, who occupied virtually the rest of the province, had already built a railroad which would give the British access to its inland areas. Much of Shandong had suffered years of drought and the possibility of earning foreign money would give peasant farmers a lifeline out of poverty.

Canadian doctor Harry Livingstone, responsible for labour recruitment,

visits a rural area of China

Notices were put upthroughout the rural regions and missionaries active in the province played a major role in publicising the fact that the British had come in search of able-bodied men. Applicants would first go to the nearest labour bureau, then report to the main recruitment stations, where they would have to go through a series of rigorous health checks.

Eye examination

Having subsisted on a poor diet all their life, many suffered from ill health and failed to pass. Trachoma and conjunctivitis were common diseases and ones which would plague the Chinese labourers abroad. Successful candidates would be transported to Weihaiwei and, while waiting for the next ship to arrive, would undergo intensive military training.

Thumb prints on registration at Qingdao

Vaccination against typhoid

Training at Weihaiwei

CLC musicians preparing to leave for Europe

The journey to Europe

The first shipment to leave the shores of Weihaiwei was in early 1917. To avoid further attacks from German U-boats, they were taken on a circuitous route by ship across the Pacific to Vancouver in west Canada, where they were put into sealed carriages - partly to avoid payment of the head tax levied on immigrants – and continued by train for several days before reaching Halifax on the east coast.

Train journey across Canada

From there, they took another ship to Liverpool or Plymouth, before they finally crossed the Channel to northern France. Most of these men had never been on the high seas before and many suffered bad bouts of seasickness. Conditions in the hold were cramped and, in the summer, unbearably hot. Some died en route and were either buried at sea or in the cemeteries of Liverpool, Plymouth and Folkestone.

On board ship

Finally, on 19th April 1917, after a gruelling three-month journey, a thousand Chinese men arrived in Le Havre, France, weary and bewildered. This was the first batch of the Chinese Labour Corps (CLC). They would be followed by several tens of thousands from mainly Shandong – in total 94,574 according to the medal roll. Together with the French contingent numbering over 40,000, the Chinese formed the largest foreign labour corps involved in the Great War. (More would have been recruited, had there not been a severe shortage of ships during the last year of the war.)

Unloading guns at Calais docks

Clearing rubble

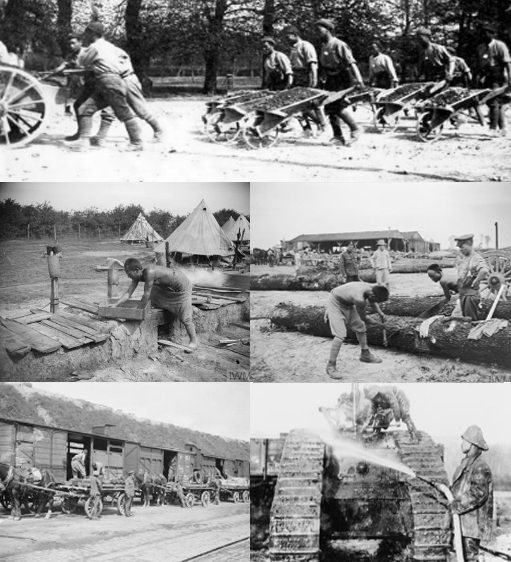

Life behind the lines

Pagoda built by CLC at their hospital in Noyelles-sur-Mer

The CLC was based at Noyelles-sur-Mer in northern France at the mouth of the River Somme. They had their own hospital and were housed in barracks, but these were fenced off from those of the soldiers. Fraternising between British and Chinese was forbidden by the Controller of Labour, because “it caused a loss of prestige and much decreased efficiency”. The labourers did heavy work, unloading guns, building roads and railways and digging trenches; many were skilled and worked in the munitions factories or helped with repairing army tanks. Field-Marshal Douglas Haig, who was in charge of the British Expeditionary Force during the war, remarked admiringly: “By Jove! I wish I had a whole army of those chaps, properly trained!”

A typical CLC camp in France

The men were organised into battalions and companies and supervised by junior gangers who in turn came under senior gangers. Their contracts, spanning three years, stipulated that they work ten hours a day without respite, but the pay was worth it. They received one franc a day in Europe (or 1.5 francs if they were a ganger), while their families back in the village were given 10 silver dollars per month (or 15 silver dollars in the case of gangers). This arrangement was made to deter the men from squandering their wages on gambling, a serious addiction that would land many a worker in debt. Coarse and illiterate, lack of communication between them and their commanding officers would often give rise to conflict and violence. For example, tempers flared when they mistook the order ‘Go!’ for the Chinese word for ‘dog’ (gou). Misbehaviour led to severe beatings or imprisonment and, in extreme cases, execution – despite the fact that they were not military men.

Labourers open savings accounts

To avoid potential misunderstandings, language lessons became essential and British and Canadian missionaries - some from the YMCA - who had previously worked in China, were put in charge of teaching them English, while Chinese students on the Work-Study Programme in France (留法勤工俭学会, liu fa qingong jianxue hui), advocated by the great educationist Li Shizeng, were enlisted as interpreters and tutors in the Chinese language, enabling the men to write letters home – something they would probably never have been able to do back in their own country.

Mail arriving

Food was another point of contention. Unused to bread and ham, both in terms of taste and size of helping, the men created a rumpus and would not be appeased until they were given the freedom to buy their own provisions, run their own kitchens and fend for themselves.

Though mocked for their strange language and customs, their dragon dances, stiltwalking and folk dancing at Chinese New Year provided much-needed entertainment for the Allied troops.

Chinese New Year celebrations

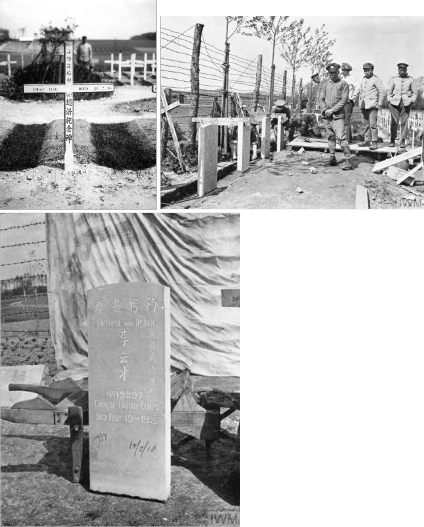

Yet danger was always around the corner. Though given the guarantee they would never be at the front line, Chinese labourers would pull armaments or blow up unexploded shells. Worse still, when Armistice was declared in 1918, while British soldiers returned to England, the CLC stayed on and were given the dangerous and gruesome task of clearing mines and burying the dead.

It was not until 1920 that most of them finally set off for home. They did not have the option to stay behind, as did some of the French recruits, who settled in France and formed the origins of Paris’ Chinatown.

Betrayal at Versailles

A total of 140,000 Chinese labourers had served under the British and the French. Yet, despite this massive human effort, at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, China was denied a voice. Britain and France had both made secret pacts with Japan, promising to back its claim to all German concessions in Shandong in return for Japanese military support in Jiaozhou Bay and patrolling the Atlantic against U-boats (although, curiously, not a single Japanese destroyer was attacked). More shockingly, it transpired that China, too, had signed an agreement with Japan with the same conditions. Japan had steadily increased its sphere of influence in China and tried to impose the ‘Twenty- One Demands’, which would extend Japanese rights in the country. At first, China would not accede to the terms, but Yuan Shikai, then president of the fledgling Chinese republic, finally signed a diluted ‘Thirteen Demands’ in May 1915, ceding all German holdings in Shandong to Japan.

Three years later in May 1918, impoverished and unable to secure financing from the Western Allies, China signed yet another agreement – the Sino-Japanese Military Alliance – granting Japan the right to station troops in Shandong and control the railway in return for a loan of 20 million yen.

Ironically, the Chinese delegation attending the peace talks were totally ignorant of the secret deals. In fact, Wellington Koo, who was Chinese ambassador to the States, made an impassioned argument for the return of Shandong on the basis of it being the cradle of Chinese civilisation and the home of China’s great sages, Confucius and Mencius. His speech fell on deaf ears. While American president Woodrow Wilson had been sympathetic to China’s cause, the British and French prime ministers David Lloyd George and Georges Clemenceau would not give it a thought. Arthur Balfour, Britain’s Foreign Minister, was positively scathing of China, stating that it did not deserve to get its territories back, for its participation in the war had involved “neither the expenditure of a single shilling nor the loss of a single life”. As for the Japanese, they had attended the conference with a clear goal in mind and were determined not to budge. So it was that the Allies decided to transfer control of Shandong Province from the Germans to the Japanese – a worse enemy in the eyes of the Chinese.

When news of this outrage reached China, the students of Beijing marched to Tiananmen Square on 4th May 1919, protesting against the government’s ineffectualness before the Allies and its incompetence in handling the peace negotiations. Their rallies sparked further student demonstrations and workers’ strikes nationwide, which grew into a huge popular upsurge in nationalism that became known as the May Fourth Movement. This would subsequently give rise to leftist thinking and eventually lead the country on the road to communism. The Treaty of Versailles was never signed by China.

May Fourth Movement

As the Chinese political reformer Kang Youwei had warned when advocating against China’s involvement in the world war: “There is no such thing as an army of righteousness which will come to the assistance of weak nations.”

Return to China under Japanese occupation

All these political transactions were taking place under the very noses of the Chinese labourers as they were burying the dead in the cemeteries that now dot the rural landscapes of northern France and Flanders. Upon their return to China, while some were able to buy land and start businesses with their savings, many discovered their homes had been burned and schools closed down by the new ruling power. Imperial Japan had come to subjugate China and would remain there until its own defeat in the Second World War.

The labourers were unable to take much back with them, apart from the odd uniform or an item of cutlery. These have all but disappeared with the passing of time. The only significant reminder of their service under the British are the bronze medals issued to each of them at the end of the war (and only at their own insistence), the single mark of personal identity on them being a roll number. A handful were awarded the Meritorious Service Medal and Royal Humane Society Bronze Medal for acts of exceptional bravery. Despite universal praise for their outstanding work, however, they were largely forgotten once they left European shores.

Legacy

To add insult to injury, in the Panthéon de la Guerre - a monumental piece of art executed by French artists shortly after the outbreak of war to depict, in anticipation, a victorious France and its courageous allies – the Chinese Labour Corps, originally appearing next to representatives of other nationalities, were later painted over to feature American troops. So China was not only humiliated at the Paris Peace Conference; its contribution to the Allied effort has effectively been erased from memory.

At least two thousand who worked for the British died from shellfire or disease. A Chinese cemetery was built in their memory in Noyelles-sur-Mer in northern France. A monument has been erected near the battlefields of Flanders.

Here in Britain, there is nothing – no mention of the Chinese Labour Corps; no recognition of the part they played in the Great War; no memorial to those who gave their lives to a cause about which they knew little.

The aim of our project is to raise awareness of the vital role played by the CLC in World War I and to build up a legacy of collective tokens and memories to honour their contribution and serve as a remembrance, for future generations of British and Chinese alike, of these simple men who left their homes in the Far East, some forever, to travel to the alien West and who toiled through those years of our turbulent past to help create for us a peaceful today.